Being a Mensch

By Olaf Möller

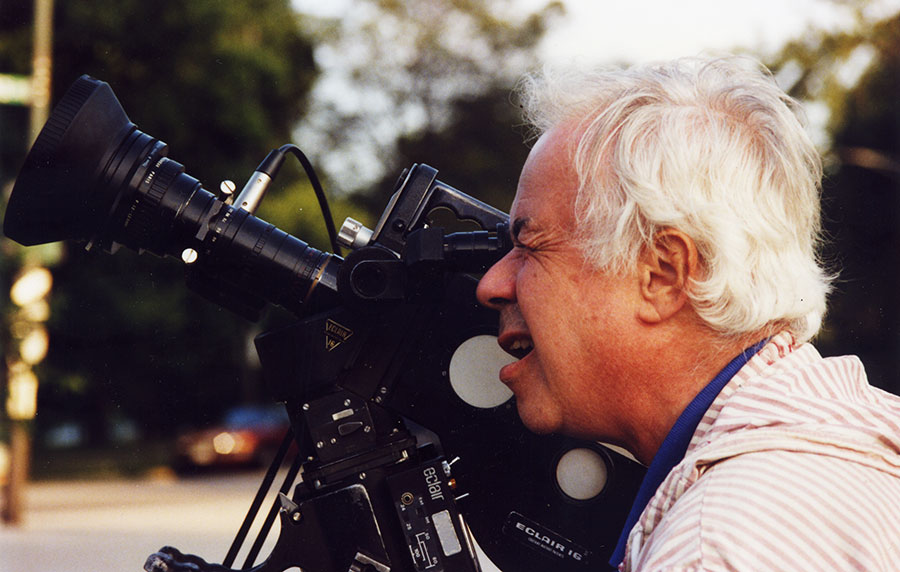

Right from the start, Manfred Kirchheimer was recognized as a major filmmaker – and yet, over the course of a career now easily six decades long, he got never championed, cultivated, turned into a name, an auteur whose latest work was always eagerly awaited.

The reasons for this are several and have to do with the infrequency of his output as well as some works’ length which made them difficult to distribute or program inside conventional structures. Yet the probably most important one is that Kirchheimer’s cinema was never fashionable in terms of style. When he debuted with Colossus on the River in 1963, direct cinema was all the rage – an aesthetic as well as politic of images and sounds that never held any promise for him. If one wants to put it in slightly polemical terms: direct cinema is all about society as spectacle, a liberal-minded play whose outcome might change from time to time but not the rules – while for Kirchheimer, human endeavour, mankind itself is but fleeting, as can be witnessed, by the way, in eg. Claw. A Fable (1968) or Up the Lazy River (2020). New York is shown as almost growing from primeval forests to a City on a Hill whose future as a ruin overgrown with grasses, ferns and trees is already visible to the curious eye. The biblical reference is apt as Kirchheimer loves to show the older architecture of New York in a way that stresses its similarities with Gothic cathedrals inhabited by gargoyles galore – reminders of the unchanging nature of human glory and misery to those who pay attention to their all-knowing stony silence.

Kirchheimer loves grandeur, maybe because it’s created by those tiny beings called humans. Colossus on the River is almost an essay on that particular relationship: the SS United States – the biggest ocean liner built in the USA as well as the fastest ship in the world of its kind – is manoeuvred into New York Harbour by a pilot commanding a handful of tugboats. The contrast is staggering: one man able to read the language of clouds and waves directs a bunch of small vessels to do cautious yet decisive minuscule movements that will protect the safety and integrity of a steel behemoth and the thousands that made it their temporary home – all under the watchful eyes of its intellectual father, naval architect William Francis Gibbs, who, the commentary claims, is always there when the ship arrives home. An ocean liner coming in from an Atlantic crossing was still a rather ordinary sight to New Yorkers of the time – and yet, the writing was on the wall: this mode of travelling won’t be too long any more for this world. Six years after the film was made, the SS United States got withdrawn from service after its 400th journey – air travel had taken over by then. It’s difficult to not read any deeper meanings into all this, including the demise of American power and influence in the world – towards the end of ’63, President Kennedy will be assassinated, while the war in Vietnam escalates and escalates. The film’s maybe most overwhelming shot shows a Black sailor against the gigantic Stars and Stripes floating in the wind – a last salute to an empire collapsing.

Did Kirchheimer arrive in the United States on a ship like the SS United States? After his birth in Saarbrücken in 1931, his family left the German Reich in 1936, when it became only too clear how serious the ruling Nazi party was about its policies subjugating the nation’s Jewish citizenry – extermination wards. Was that writing also on the wall? Thus, the Kirchheimers made New York their new home. How much of Saarbrücken did stay with Manfred Kirchheimer, how much does he remember of his first years in that other country?

Kirchheimer went to school in New York, and then to university there as well, where his mentor was another German émigré: Dada pioneer and abstract animation axiom Hans Richter, who founded the City College’s Institute of Film Techniques. While Richter was certainly of significance for Kirchheimer as he put him on his tracks, the practical experience he gained from working with Leo Hurwitz in the 60s was probably more important for his filmmaking practice. Hurwitz’ Essay on Death: A Memorial to John F. Kennedy (1964) certainly shows a deep kinship between the two in the way nature is shown and dramatized, and how the evanescence of life gets stressed by the presence of gargoylesque shapes as well as artworks like Richard Lippold’s 1953 sculpture Variations within a Sphere, #10: The Sun to whom and which they’d dedicate a film of its own two years on. Playing a co-responsible role, they appear among dozens of others, avant-garde luminaries mostly, on the long contributors roll call for the 1967 agitprop monument For Life, Against the War.

The following year would see to the release of Claw. A Fable (co-director: Walter Hess), the film to establish the Kirchheimer mode of expression most widely celebrated: the symphonic choreography of images and sounds, which also characterizes Bridge High (1975; co-director: Walter Hess), Stations of the Elevated (1980), in some chapters Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan (2004) and Art Is… The Permanent Revolution (2012), and then again the whole and all of Dreams of a City (2018), Free Time (2019), Up the Lazy River and One More Time (2021), the latter four made in good parts using material from his earlier films and shoots. Kirchheimer establishes himself here as a heir to the likes of Walter Ruttmann, Albrecht Viktor Blum or the Kaufman family in its aesthetic diversity – while going one or two steps further than all of them by making time, considered at an epic scale the subject of his montages, which sometimes takes the shape of the above described movement from the antediluvian to the high modern, then othertimes crystallizes into something so basic yet fundamental as the sprayed trains moving through the urban vastness as signs of the times to come – the writing is here quite literally on the walls; in his most recent works, time as a subject is ingrained in the textures of the images themselves, just as it is in the fashions of the days or the buildings one now knows to be gone. This mode, with its carefully created soundscapes and dramatic imagery that proudly shows Kirchheimer’s fascination with the graphic glory of printing art, is closest to what one calls pure cinema.

That said: Kirchheimer’s arguably richest works are the formally more complex ones, which always means that to some degree they do use language in a rich and evocative way, starting with Colossus on the River, then his magnum opus We Were So Beloved (1986), to finally Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan and Art Is… The Permanent Revolution. Mind that these aren’t his only films to work with words – Daughters (2020) eg. is almost only words, while his lone foray into fiction, Short Circuit (1973) has a lot of dialogue even if it’s headed towards a long montage sequence in the protagonist’s head that uses almost exclusively sounds and images to suggest his growing anxieties and paranoia – his bourgeois racism.

Which connects it uneasily yet intimately with We Were So Beloved, a portrayal of the Jewish émigré community in Washington Heights at the far end of Manhattan – the world of Kirchheimer’s family whose memories and opinions form the film’s core. Almost everybody here has lost next of kin to the Nazi death machine; some even survived being deported into an extermination camp. But as Kirchheimer has to find out: having escaped one of the 20th century’s worst atrocities didn’t humble everybody into a better human being – prejudices, eg., are still there, with the Blacks of neighbouring Harlem getting sometimes perceived in ways not too dissimilar from that of the Polish and Russian (later Soviet) Jews back in Germany during the 10s, 20s, 30s: backwards and/or poor, in that a threat to their own position in society, the way they (still) feel perceived by the goyim majority. In many ways they remained who they always were – history barely touched them. And as Short Circuit, which can be read as a tacit portray in grey and black of Kirchheimer himself, brutally suggests: even trying to bridge the gap, trying to overcome divides of class and race, can be perceived as condescending by those who try. The only thing that remains to do is to go with the acts of solidarity and support, and to swallow the darkness inside wholly and totally, for in the end, this is also only another form of self-loathing and -pity, and also pride – emotions that never helped anybody. It thus fits that Kirchheimer found out only after finishing We Were So Beloved that some things were more complicated than his interviewees let on. In a very often quoted scene his father says that he’d probably not have saved anybody, for he thought of himself as a coward; only later did Kirchheimer learn that his father did shelter a fellow Jew on the run for a night; obviously he thought this was nothing – which gives an idea of what courage meant to this one man: a lot. Mind that Kirchheimer never goes Lanzmann or Ophüls in the way he presents his family in particular and the Washington Heights community in general: he might voice his opinions and thoughts, and towards the end of the film certainly summarizes his insights, but he’s never overtly judgemental – while he might sense some capital-t truths he’s too humble and generous, too much a Mensch to condemn others. And while he voices his disdain for all the Germans who collaborated with the Nazis if only through their passivity, he lets several US Americans his own age talk about this country’s history of persecutions, and how its citizens too often failed under far less terrorizing circumstances.

Humans are mainly weak – and yet, as a collective they can very well defy their insignificance to create culture and progress, grow together beyond the boundaries of one, claim dominion over realms of the spirit and the soul their forefathers often would not have been able to conceive. On a formal level Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan and Art Is… The Permanent Revolution might be the more refined, multi-layered and ever-surprising achievements of Manfred Kirchheimer – but when it comes to the human spirit, few ever saw more greatness in it than he did in We Were So Beloved.

Colossus on the River

The tides, shifting winds, and cross-currents in New York harbor, make the docking of a huge ocean-going liner a series of tricky maneuvers. This exuberant film shows the skill and delicacy required in berthing the legendary ocean liner “SS United States”.

Claw

As a terrifying machine demolishes buildings to rubble, Claw, bores into the ill effects of urban renewal and destruction. In this lyrical documentary, the human-like stone reliefs on older buildings watch the city being altered by the great machines which will finally destroy them, too.

Short Circuit

Kirchheimer’s only semi-narrative film.

In his apartment on the corner of 101st Street and Broadway, a documentary filmmaker begins to question his interactions to the white family and black workers he shares his daily existence with. Staring out his window he begins to drift and fantasize a parallel life, which turns into a complex sound and image montage of street photography depicting a longsince vanquished Upper West Side. Full of doubt, a lifelong city resident looks at his liberalism and doesn’t like what he sees. Constructed reality and documentary fiction, an unclassifiable masterpiece of ideas and technique that by all rights should be considered a landmark, had it not been virtually impossible to see.

Bridge High

Bridge High is an evocative passage across a suspension bridge. Moving from the country to the city, the film expands the half minute it takes a car to cross, into a nine-and-a-half minute trip, choreographing cables, girders and arches into an exuberant dance.

Stations of the Elevated

A Cinema Conservancy Release, in association with agnes b., of a Streetwise Films Production.

Stations of the Elevated (1981) is a 45-minute city symphony directed, produced and edited by Manfred Kirchheimer. Shot on lush 16mm color reversal stock, the film weaves together vivid images of graffiti- covered elevated subway trains crisscrossing the gritty urban landscape of 1970s New York, to a commentary-free soundtrack that combines ambient city noise with jazz and gospel by Charles Mingus and Aretha Franklin. Gliding through the South Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan – making a rural detour past a correctional facility upstate –Stations of the Elevated is an impressionistic portrait of and tribute to a New York that has long since disappeared.

We Were So Beloved

Between 1933 and 1941 thousands of Jews from Germany and Austria fled to America. Leaving behind brothers, sisters and parents, more than 20,000 of them came together in Washington Heights in New York City. It became a German Jewish enclave dubbed by the Americans who lived there, “The Fourth Reich” or “Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson.

The film probes the emotional and philosophical outcome of their survival.

TALL: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan

TALL is the story of the unstoppable rise of the skyscraper. Starting in 1869, in New York and Chicago, elevators, steel, and electricity combined to create a frenzy of tall and taller buildings. Fierce rivals competed for favor, money and power. The ultimate showdown between the Chicago architects Louis Sullivan and Daniel Burnham –between integrity and accomodation – changed the future, shaping the modern skyline throughout the world.

Dream of a City

This astonishing new film, comprised of stunning black and white 16mm images of construction sites and street life and harbor traffic shot by Kirchheimer and his old friend Walter Hess from 1958 to 1960, and set to Shostakovich and Debussy, is like a precious, wayward signal received 60 years after transmission.

Free Time

An hour-long paean to simpler days, to the beautiful neighborhoods of the New York City of yesteryear, and to the way we used to spend our time.

One More Time

A coda to the triptych, providing a final, glorious look at the singular archive of footage shot over decades in and around New York City. A combination of black and white and color footage, all never before seen, dating from the earliest shoots through Stations of the Elevated. The intercutting of material, separated by years, provides not only a comparison between New York then and now, but a free associative recollection of anyone who has spent their life walking down the same streets, seeing the world change around you, every corner and building reminding you of a half-forgotten memory.

Up the Lazy River

Crafted from the endless wealth of images filmed in 16mm on a Bolex by Kirchheimer and Walter Hess, Up the Lazy River is the conclusion of the triptych begun with Dream of a City and Free Time. Beginning with paired images of boulders planted in the middle of the urban landscape and outside the city, the connection between the beauty of the city and the natural world begins to form. There are modern skyscrapers above, and the horse-drawn carriages below. The film is filled with motifs that Kirchheimer has made his own: the camera traveling majestically through buildings, pointing skyward, light reflecting off glass, sweeping through the streets filming storefronts and daily life, always with an uncanny ability to capture small moments between neighbors, and the faces of a metropolis, culminating to the ecstatic sound of Louis Prima and the peaceful sounds of the river. Look close: you will even catch a glimpse of Manny himself.